The martial art we today call karate was originally developed in the Ryuukyuu Kingdom (located at an archipelago between southeast Japan and southeast China), based on the traditions and fighting knowledge of that area’s natives, plus the influences coming from arts and masters from other Asian regions (with some prominence to the arts from the south of China, among others). The result of such a combination was the creation of a complete and remarkable bulk of knowledge, traditions, methods and techniques of great effectiveness in physical fighting contexts aimed at the protection of the physical integrity and the lives of the practitioners, as well as those of the persons under the practitioners’ guard.

That art started being transmitted publicly and to large groups of students only in the first decades of 20th century. Karate, which originally used to be taught only in secrecy to specific students who enjoyed the trust of ancient masters, was finally presented to the public on occasion of its introduction in Okinawa’s school system as part of Physical Education discipline[2]. Approximately two decades later, the martial art from the Ryuukyuu Kingdom started being gradually introduced in martial arts schools and universities of mainland Japan – which at this point had already annexed that ancient kingdom (now identified as Japanese prefecture of Okinawa) to its territory.

Karate acquired popularity throughout the years, becoming one of the most widely practiced martial arts of the world. However, as years passed, and within the context of mass transmission to new students, a historical process involving several factors resulted in deep modifications in the content of that martial art which was previously only taught secretly. Among the factors that influenced the modifications we can mention, without exhausting the list: the remains of the ancient culture of transmission under secrecy (old masters would refuse to teach the complete art to new students); the effects of World War II over Okinawa and Japan (death of many practitioners and destruction of a great part of Okinawa, and the prohibition, by the occupying forces, of the practice of martial arts by the Japanese); the cultural changes affecting the eastern martial arts (that regardless of originally having been deadly fighting systems, were now adapted to become forms of physical, moral and civic education, sport and artistic/esthetic expression – thus overshadowing the old methods and goals). As a result, a great part of the original teachings of karate was deeply distorted, badly transmitted to the students and future instructors, or even forgotten – and the information about ancient karate went on to become increasingly rare, leading to the near extinction of much of its most valuable knowledge[3].

So, modern karate has differed deeply from old karate and, because of circumstances, the majority of karate schools in the world was left to teach an art full of gaps and little faithful to the deep and effective original fundamentals of physical fighting (resulting in great loss to the utilization of karate as a self-defense system). It’s as if the product offered modernly was like a jigsaw puzzle where many pieces are missing (and for that reason many other pieces just don’t seem to fit) – and the resulting image of that puzzle cannot be understood, if we look at it trying to see the old idea of a self-defense martial art. Many adepts of karate had understood those changes as natural and inevitable, because in their view the ancient knowledge was unnecessary in modern world – and the transformation of karate in a mere fighting sport and physical and moral education method (even if keeping important principles from the tradition of Japanese modern budo) would be an evolution to the art. It is also worth noting that a similar process also happened in the foundation of modern versions of the majority of traditional martial arts, including those of Japanese origin[4]. At one point, most practitioners and even instructors already ignored that distinction (between old and modern martial arts), not perceiving or not really caring about the fact that the karate they had learned did not accurately match to the martial art originally practiced in the Ryuukyuu Kingdom (Okinawa) – even though many old masters had emphasized the existence of these differences[5].

But not everyone was resigned with the idea of leaving behind the old teachings of karate. Throughout the 20th century and especially in the recent decades, karate masters from Okinawa, along with scholars from all over the world, initiated an effort to rediscover this martial art. Many researchers started to travel to the region where karate was born, to study the oral teachings and documents left by the great masters of the past, and to learn with the local masters; masters of that region also decided to finally share secrets that until then had become rigorously kept[6] – to make sure that old style karate would not die, and to reverse the process of deformation it had been through. That movement acquired global proportions in the recent years, boosted by the revolution of communications and by the hard work of researchers determined to retrieve information and transmit it to the world. Societies were created aimed at researching, preserving and promoting Okinawan “old style” karate, and the knowledge started flowing in circles of practitioners throughout the world.

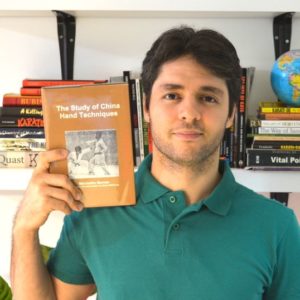

Within this context, Brazilian researcher Samir Berardo founded the Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai – a society of passionate practitioners, with the objective of practicing, researching, preserving and promoting karate in its original form and fundamentals, as an art of self-defense and life preservation. This society carries out research projects and offers to the public a base of knowledge that leads to a deeper understanding of old style karate, through the publication of written works and providing of direct instruction (classes and seminars) – everything with the deepest respect for each and every one those who dedicate themselves to karate and for the general public. Muidokan also maintains contact and exchanges with several great instructors, researchers and practitioners around the world, and develops, through the work of the founder Samir Berardo, an unprecedented and notable project on the recovery of the original fundamentals of the art, especially in the area which is probably the most fascinating and misunderstood in karate: the study of kata, its meaning and its applications (study popularly known as bunkai).With the advent of this global process, karate today is going through a real revolution and a return to its origins, and Muidokan, its associates and supporters are a part of that revolution. If you love karate and want to know, practice, promote and help preserving the thorough and original fundamentals of this art, you can also be a part of that great movement, associating, collaborating with us or merely by getting to know our work and showing your support (following us and sharing our posts helps a lot!).

Notes:

[1] Karate (空手) is currently the most commonly used name to refer to the martial art we are talking about here. However, historical accounts have reported the use of other names, such as: “toude” (唐手, which can also be pronounced as “karate”); “te” (手); and terms and combinations between them. Also, note we are using here the romanization corresponding to the Japanese language pronunciation, not to that of the Okinawan native languages (for example, in Uchinaaguchi – language then used in Shuri-Naha area – “toude” and “te” are pronounced as “toudii”/”tuudii” and “tii”, respectively). Although “karate” is currently the most well-known expression, some schools have continued to use other names, and some of them use them to the present day, and at times defend the return of the names considered as older. We will get back to this topic on a future article.

[2] The inclusion of karate as part of the physical education program of Okinawan schools was the result, among other factors, of the efforts of master Anko Itosu (one of the teachers of famous Gichin Funakoshi, and founder of famous kata: Pinan, Kusanku Dai and Kusanku Sho – also known in Shotokan karate versions as Heian, Kanku Dai and Kanku Sho). Itosu acted at first as karate instructor in Shinjo Elementary School, in Shuri (Okinawa Prefecture), and later extended his teachings to other schools, and then proposed, through a letter to the prefecture’s Department of Education, the introduction of karate in all schools of that prefecture – and then hopefully in all Japanese schools. It is important to note that, as we see later in this article, the kind of karate offered in Okinawan schools in this first moment was already quite different from what used to be taught privately to the masters of the previous era. So we note that from the very first stage of the massification of karate education the art was already no longer taught strictly as a fighting system, but instead as a mere form of physical education. And that “school karate” was exactly what served as main model to what would later be taught in mainland Japan and the rest of the world.

[3] For example, old style karate, different from the modern version, was filled with maneuvers which would be considered as “grappling” techniques, such as joint locks and throws. Although today more and more of people are becoming aware of this fact, we know this kind of technique has received very little to no attention in the vast majority of modern karate schools in the 20th century – that would concentrate mostly in the teaching of fist/arm and leg strikes, and “blocks”. In addition to the grappling techniques, many other important aspects of this art have also been deeply neglected in the mass teachings of karate schools throughout 20th century. In this sense, one following quote by Kenwa Mabuni (founder of Shito-ryu karate and another pioneer who brought karate from Okinawa to Japan) is extremely relevant – he not only explains that throws and joint locks are an integral part of karate, but also emphasizes that karate as was being taught in that time (1938) in Tokyo did not represent the art in its entirety – what would lead students to misunderstand the art. He also urges karate practitioners to avoid narrow-minded thinking inside the confinements of a single school of style – an advice that remains important to this very day. In Mabuni’s words: “As up to now [1938] karate has only partly been introduced in Tōkyō, people who exercise karate in Tōkyō believe that it solely consists of atemi (impact strikes) and kicking techniques. When talking about gyaku-waza and nage-waza they assume that these only exist in jūjutsu and jūdō. This way of thinking is exceedingly counterproductive with respect to karate itself and can only possibly be attributed to a lack of knowledge. In any case, with respect to the propagation of karate-dō it is exceedingly disappointing that only a small part of the entirety of karate had been introduced in Tōkyō. To those who have the future of karate-dō in mind I recommend to under no circumstances narrow-mindedly hold on to the ‘nutshell’ of a style and a school, but rather to synthetically explore karate as a whole“. [MABUNI, Kenwa. “About Gyaku and Nage (Locks & Throws) – The Need to Study Gōjū-ryū” (1938). English translation by Andreas Quast: http://ryukyu-bugei.com/?p=5285].

[4] Following the historical changes in society, that process happened to old martial arts of all parts of the world. Accordingly, a lot has been lost (and now many people are trying to restore it) in medieval/ancient martial arts from Europe, China, Siam/Thailand, and even from Brazil (with Brazilian capoeira, which originally had a much more deadly and pragmatic nature but was less esthetic or athletic). This does not diminish the importance of any of these martial arts in their modern versions (that are in most cases geared towards esthetic or sporting applications but not seriously for deadly fighting). Just what happens is that begin to understand that the modern arts are very different from their old counterparts. In Japan, the old kenjutsu (technique of the sword) gave place to the modern kendo; the old jujutsu (sometimes romanized as jujitsu) originated the modern judo; and so on with several old martial arts. Still talking about Japan, this paradigm shift is known as the change from the arts of Koryu Bujutsu (old style martial arts) to Gendai Budo (modern martial way).

[5] In this sense, check a commentary from Funakoshi (originator of Shotokan karate and one of the great pioneers that brought karate from Okinawa to Japan): “More than twenty years have passed since I first brought karate to Tokyo. Today, not only those involved in athletics and the martial arts, but also people in general have at least heard of karate. Even so, the number of individuals who really understand the nature of karate is extremely small. Furthermore, since karate is ever advancing, it is no longer possible to speak of the karate of today and the karate of a decade ago in the same breath. Accordingly, even fewer realize that karate in Tokyo today is almost completely different in form from what was earlier practiced in Okinawa”. [Karate-do Nyumon, 1943].

[6] There are multiple accounts about masters of previous generations who only in the last portion of 20th century (generally after becoming quite old or approaching their passing time) have decided to finally take to the public teachings which were received originally in secret (and there are also accounts of masters who took those teachings with themselves to the grave). As an example both about the culture of secrets and the change of attitude of Okinawan masters in more recent times, check the excerpt of a story told by Seikichi Toguchi, student of Choju Miyagi (founder of Goju-ryu karate): “Chojun Miyagi taught me this theory just before his death and recommended that I not make it public. However, as karate has become popular around the world, I felt it would not benefit true karate if I were to hide it [the teachings he transmits in his book] as a secret in my shorei-kan school. I regret that the public has lost confidence in traditional Okinawan karate and may not understand the true value of karate kata”. [Okinawan Goju-Ryu II: Advanced Techniques of Shorei-kan Karate. California: Ohara Publications, 2001].

[7] Karatejutsu no Kenkyuu (“The Study of Karate Techniques [“China Hand” Techniques]”, in a free translation) by Morinobu Itoman is one of the best works ever written about old style karate, written by someone who learned it in the old fashion and used daily as a law enforcement officer in the streets of old Okinawa (more about this work on a future article). It is possible to purchase the excellent translation published by Mario McKenna in http://www.lulu.com/shop/morinobu-itoman/the-study-of-china-hand-techniques/paperback/product-20649437.html

Photo credits:

In the beginning of this article: Karate training with Shinpan Shiroma (Shinpan Gusukuma) in front of Shuri Castle, Okinawa, 1938. Wikimedia Commons. Original photo, in black and white, published by Genwa Nakasone in Karate-do Taikan, 1938. English translation (“An Overview of Karate-do”) by Mario McKenna, available for purchase in the website Lulu.com and present in the personal collection of Samir Berardo.

Pingback: Self-defense: A theme to face with much more seriousness

Pingback: What is old style karate? – Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai