Here is an article written by Muidokan member Bruno Chagas, originally published on his blog, Puro Karate. The text addresses kakedameshi, kake-kumite and kakidī, historical concepts of Okinawan karate. The material is extensively supported by historical references and accounts, presenting invaluable descriptions of the practices. It is crucial information for understanding the fundamentals of karate within its original context and purpose, and therefore of great relevance to the karate community as a whole.

Bruno also published a video summarizing aspects covered in the article, which can be watched at this link.

In Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai, the concepts described in the article written by Bruno have been extensively studied and applied for years, with their depth and functionality attested in practice and associated with a careful and rich research into the applications of kata. Thus, the material reinforces the historical foundations and the reliability of the work developed by Samir Berardo and by the members of this research society.

Text originally published on 8/31/2021, in Puro Karate

🇧🇷 Se você está procurando a versão em português, clique aqui.

🇪🇸 Si está buscando la versión en español, haga clic aquí.

You have two options for reading: downloading the PDF version, which is more easily readable (considering the article is long), or the plain text on this page.

Enjoy the reading!

PDF VERSION

FULL ARTICLE

Kake-Kumite/Kakedameshi: The original free sparring of Karate

Have you ever heard about kakedameshi or kake-kumite? If not, don’t feel alone, because few people have heard, much less people know what it is and even fewer have trained it inside a Karate dojo. However, these words started to be mentioned more frequently and explained due to the increase in interest in the history of Karate. Kakedameshi and kake-kumite are part of the historical elements that make up Karate since the time it was called in the native language of Okinawa (uchināguchi) Tōdī 唐手[1] (Chinese hand; Tōde in Japanese) and refers to concepts even older than that, despite having become obscure due to the changes of course imposed by the modernization of the art.

Kake-kumite and kakedameshi (which is a better known word) are basically a form of free sparring (jiyū-kumite). These are an ancient type of kumite, related to the very origins of Karate. One of the main characteristics of this kumite is that it starts with opponents in contact and develops the freeform confrontation at close range. It is a very different dynamic from modern forms of kumite, which usually start and develop in the medium and long range, with a certain level of restriction in the applied techniques (sports influence) and which in most cases have little connection with the techniques represented in the kata.

Throughout this article, I will present definitions of kake-kumite and kakedameshi, related terms, as well as a series of historical and modern records on the practice, then outlining a definition of what this type of kumite is and what its main characteristics are.

1. Terminological differentiation between kakidī, kake-kumite and kakedameshi

The old kumite format I refer to in this article has more than one denomination, depending on tradition or purpose. In Motobu-ryū it is called 掛け手[2], read in Japanese as kakede or kakete and in uchināguchi as kakidī. This term is related to the position taken at the beginning of the confrontation, in which the opponents remain with their right forearms in contact, in a crossed manner. It means something like “hanging hands” or “hooked hands”. However, the term kakete is not restricted to this position or to the specific name of the kumite, as it has a broader connotation.

Besides being a term used in Karate to define a series of techniques classified as receiving techniques (uke 受け), kakete is also present in the martial arts of southern China (called Guà Shǒu 掛手) and is related to an important concept, called “bridges” (Qiáo). As defined by Russ Smith in his book Principle-Driven Skill Development: In Traditional Martial Arts[3]:

In southern styles, the forearms are referred to as “bridges” (橋), and the act of applying techniques with the arms against the opponent’s arms is called be “bridging”, as they (in effect) connect our torso with our attacker’s.

(…)

Note that a bridge is created any time limbs come into contact, regardless of the intention or label attached to that motion. Two common scenarios typically create a bridge. The first is when the practitioner attacks which causes the defender to block. The second involves the practitioner blocking an opponent’s attack.

This concept described by Smith is totally related to Karate and the way in which old kumite is developed, as can be seen throughout this article. It is also linked to Karate concepts such as hente 変手 (strange/transforming hand)[4] and kake-ai 掛合 (harmony of contact), described by Shigekazu Kanzaki (Tō’on-ryū) as “the ability to use techniques in harmony with each other, especially in close-quarters.”[5] Relevant information is also that the concept of bridges is used in the styles of southern China, which have a historical connection with Karate.

Russ Smith (right) demonstrating a bridge[6]

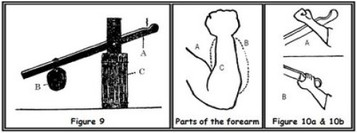

It is also pertinent to note that the connections and bridges developed in kakete are so important within Karate that they are the object not only of activities in pairs, but also of classical supplementary exercises (hojo undō 補助運動), one of the main ones being represented by the instrument called kakete-biki or kakiya[7]. It is a wooden post with an arm fixed to a lever, usually with a counterweight at one end, exactly for training techniques related to contact and control of the opponent.

Kakiya/kakete-biki

Due to the conceptual breadth of kakete/kakidī, as we can see, the term is not restricted to the specific activity of kumite, but ancient kumite was made from kakete and the application of techniques (strikes, control maneuvers, locks and whatever is most convenient for the practitioner) from the bridges. Contributing to this conceptual definition, it is also relevant that the kanji Te 手, in addition to the meaning of “hand”, is also used in a compound way in the sense of “technique” or “skill” related to a certain activity,[8] which could give a sense to the kakete of “technique/skill of hanging” or “technique/skill of hooking”.

Once the concept has been established, we can approach the next term, kake-kumite 掛け組手 (meeting of hands in kake/hook) that expresses more specifically the aspect of combat. As we know, the term kumite 組手 is a synonym for sparring in karate, and here it is specified with the term “kake”, similar to the specification of other types of confrontation such as shiai-kumite 試合組手 (competitive meeting hands), jiyū-kumite 自由組手 (free meeting hands), yakusoku-kumite 約束組手 (promised/agreed meeting hands), among others. Therefore, kake-kumite indicates the type of activity (combat) and the dynamics employed in this activity (with hands in kake). It is also important to note that kake-kumite can be considered a type or category of jiyū-kumite because of the way it develops.

Kakedameshi 掛け試し (kakidamishi in uchināguchi), in turn, means “testing through kake” and is a kind of challenge between two karateka done in the dynamics of kake-kumite. Historical references point to this term with greater incidence, since many of the reports are of challenges made in kakedameshi format involving pioneer masters (exemplified later in this text).

In short, we have the dynamics of contact (kakidī/kakete) that is applied in a specific and intrinsic way in a sparring activity (kake-kumite), and this type of sparring can be used in tests and challenges (kakedameshi). The three terms are related and cover scopes of combat within Karate. Throughout this article, I have preferred the use of the terms kake-kumite and kakedameshi based on this definition, then referring respectively to kumite by kakete in a broad sense and its specific challenge format.

Another term associated with kake-kumite is irikumi 入り組み. “Iri” has the sense of “entering” and “kumi” has the sense of “joining” or “wrestle”, which can then translate the irikumi into something like “to grapple”. The word has an inherent sense of close-range fighting. There are reports that Chōki Motobu in his youth would have trained irikumi with Kōsaku Matsumora and, on one occasion, hit him in the face with a punch[9] during training, which makes it clear that this was not merely a wrestling practice, like the sumo of Okinawa. Morio Higaonna describes irikumi as follows[10]:

Means jiyu kumite, or free sparring. In former times in Okinawa after regular training had finished, the senior students who all knew each other well would practice ‘iri kumi’. There were no pre-arranged moves (yakusoku nashi). They would practice punching, kicking, throwing techniques, choke holds, locking techniques and so on, until one or the other surrendered. Because these senior students had practiced together for many years and they were friends, this was not real fighting. Their techniques were controlled if aimed to vital areas so as not to injure each other. This type of training is still referred to by the older senpai in Okinawa, who are now in their sixties and seventies, as “iri kumi.”

Modern schools have different interpretations for irikumi, with some using the expression for a type of free kumite at medium and long distance, while others consider the term as a concept of fighting close to the opponent.

2. Descriptions and historical records of kake-kumite/kakedameshi

Much is said about how Karate/Tōdī training before modernization was different from today, which is based on the famous tripod kihon, kata and kumite. The idea that the ancient training method consisted of infinite repetitions of kata is also widespread, which we can already say is not true, or at least not a general rule. Actually, ancient methods and interpretations were different from modern ones, but kata and kumite (in the sense of a confrontation between two practitioners, applying the techniques developed from kata) historically went hand in hand.

The question of kihon is more extensive, but suffice it to say that kihon means foundation/fundamentals and is not necessarily tied to the series of exercises not directly related to the kata that are generally done today. The fundamentals are trained in many ways, but it is inherent in the art. Karate without fundamentals is nothing. Chōki Motobu states that “Ryukyu Kenpo Karate can be divided into two parts: Fundamental technique (Kihon) and its combative application (Kumite). Fundamental technique is culminated in kata, such as Naihanchi and Bassai, etc.”[11] In other words, kata is a vehicle for transmitting the fundamentals of Karate and its relationship with kumite is intrinsic.

With the modernization of Karate, mass teaching to Japanese in the mainland initially did not involve forms of free direct combat. This absence was due to political, social and cultural contexts that will not be discussed further in this article. To fill the gap of free kumite, new fighting methods for this purpose were eventually developed from university Karate clubs. According to Bō Hideo[12], about training at the University of Tokyo in the 1920s:

It consisted of makiwara thrusts, a dozen or so kata starting with Pinan, and some kumite – a simple version of today’s yakusoku (promised) kumite. Therefore, we couldn’t get enough of them, so we began to practice jiyū kumite, and to wear kendō protective gear or specially invented karate protective gear to fight each other. From Shihan Funakoshi’s point of view, this was an unacceptable and evil practice. He turned his face away and tried to stop us, but we were too bloodthirsty to listen to his words.

However, at least in the period before World War II, there was in Okinawa kakedameshi, a popular type of challenge and test of skill. It was something that in mainland Japan had become a remote memory, heard about but little understood. An example of this is the definition given by Masatoshi Nakayama (Shōtōkan) in the first volume of the Best Karate book series: “In ancient days in Okinawa, karate was based almost exclusively on the kata. It was only rarely that the power of a punch or block was measured by what was called kakedameshi.”[13]

The quote of Nakayama is important because it is a reference to kakedameshi made by a Japanese master who played a fundamental role in the formation of modern karate. However, we note that he assumes a common myth already mentioned in this article (that training in Okinawa consisted only of kata); erroneously states that kakedameshi was something rare; and gives a description that does not cover everything that is included in this practice. Despite this, the description is in line with something written by his master Gichin Funakoshi about kakete.

In his first book Ryūkyū Kenpō Karate (1922) and later books, Funakoshi states that “one may approximate the presence of strength, technique and speed of his opponent naturally by way of response in using kakete.”[14] In addition to a reference to kakedameshi (test of skill by kakete), it is also possible to observe how Funakoshi uses the term as a broader technical concept, of contact, not as the fight itself. This becomes clearer when we observe that Funakoshi also describes the hikite 引手 (pulling hand) as a variant of kakete. It is also important to note that this master emphasized that the practice of kumite and kata are intertwined, stating that “kumite should not be independent and separate from kata, since every kata is applied in kumite.”[15]

The popularity of kake-kumite/kakedameshi in old style Karate, in turn, can be easily proven. There are a number of historical records and references on the subject. They give an account of the technical description of how this type of confrontation took place; refer that well-known pioneer masters would have practiced this form of kumite; and even exemplify how the practice has endured in some modern schools.

Among the most popular accounts are those related to Chōki Motobu (Motobu-ryū). Multiple sources cite that this master used to accept challenges in the red district (Tsuji-machi). Among these sources, Shōshin Nagamine (Matsubayashi-ryū), states that “Motobu Choki often tested his skill and spirit through the ever-popular kakedameshi.”[16] Nagamine also reports that, in one confrontation, young Motobu was defeated by a practitioner named Itarashiki, who was five or six years older: “Motobu could not sleep the night he was defeated, reassessing his opponent’s technique and strategy over and over. From that time forth, Motobu devoted himself to karate with an intensity he had not previously known.”

Another account by Nagamine has to do with Motobu training with Kōsaku Matsumora (Tomari-te) who, as mentioned in the previous section of this article, trained combat with his students. Nagamine reports that Matsumora refused (at least at some point) to train Chōki Motobu in this dynamic “because he knew that Motobu would use his newfound technique over in the Tsuji that evening.”

Motobu kept kake-kumite as part of his school’s legacy. In fact, an important description is given on the Motobu-ryū website, translated into English by Andreas Quast[17]:

Kakede [literally hooked hands] (in Okinawa dialect kakidī) is and old style form of jiyū-kumite, or free sparring. It is also called kake-kumite. In this old style sparring, from the position of crossed arms (see photo at the Motobu-ryu page) techniques are freely applied.

In the Ryūkyū Kingdom era, in Shuri-te and Tomari-te (presumably even in old style Naha-te), kakidī had been actively carried out. (…) As kakidī is performed from close range, rapid reactions are required.

(…)

From the Ryūkyū kingdom era to the middle of the Meiji era, in Naha‘s Tsuji district there was a form of actual combat called kakedameshi (kakidamishi in Okinawa dialect).This kakidamishi means a ”contest of kakidī”.

In addition to the description of Motobu-ryū, it is possible to safely say that practitioners of the ancient Tōdī/Karate form that was conventionally called Naha-te had kake-kumite as an integral part of their training. In the modern schools of Gōjū-ryū, the main style derived from Naha-te, this kind of dynamic is apparently not widespread (although there are related traces), but there are accounts that describe it as a common practice in the past. Below is an excerpt from an interview with Shuichi Aragaki, a student of Chōjun Miyagi (founder of Gōjū-ryū), to Dragon Times magazine[18]:

Dragon Times: I heard that Chojun Miyagi and Choki Motobu had a fight. Is that so?

Shuichi Aragaki: Well I heard that too, but it’s best not to comment on such things. Both of them were great karate men who founded schools of karate so out of respect for them I don’t want to say anything.

Dragon Times: In the old days these fights were fairly common weren’t they?

Shuichi Aragaki: In the old days, yes. The other day I heard from the principal of an elementary school that in Koto Oyama in Shuri there were always people who would accept a challenge to fight. You know, kakedameshi. In Naha at the graveyard you could always find someone to try your skill on. Even when you were walking on the street and you saw someone coming towards you who looked strong or had an unpleasant manner you could challenge him to kakedameshi.

It wasn’t so much like an argument or a really bitter confrontation rather a test of ability. If you challenged someone much stronger or much weaker, you could withdraw. If you encountered someone your own level you could fight. It was unusual for anyone to get really badly hurt.

Dragon Times: They say that in the old days in Okinawa they didn’t do kumite in the dojo.

Shuichi Aragaki: No, they did it in the dojo and outside as well. When you left the dojo you wouldhave to be careful because people would hang around outside to pick a fight with students and see how good they were. You avoided dark alleys on the way home and always kept alert to make sure that nobody was following you.

So, according to Arakaki, combat practiced in the style of kakedameshi/kake-kumite was common in Naha both outside and inside the dojo. Not only that, but Chōjun Miyagi and Chōki Motobu would have had a clash along these lines. Also important is the aforementioned fact that the Tsuji-machi red district, where kakedameshi challenges were popular, is located in Naha.

When speaking of lineages derived from Naha-te, it is necessary to make a parenthesis. Sometimes kake-kumite/kakedameshi is compared to the kakie カキエ exercise, which is more popular in this lineage (although it exists in schools derived from Shuri-te, such as the Kyudokan[19]). This comparison is useful in terms of viewing a better-known reference, as both dynamics have technical and tactical similarities (such as the use of kakete and at close range), and some schools develop kakie in a kind of “mini-sparring”. Of course, everything in Karate is related, but kakedameshi/kake-kumite and kakie are different practices.

As pointed out throughout this article, kake-kumite has an overarching dynamic aimed at free confrontation, while kakie is more restricted and has other primary purposes, such as teaching “tactile sensitivity and connection; structural alignment; dynamic posture balance; energy transfer and other related technical qualities”, as pointed out by Samir Berardo[20]. Another example in the same vein is in the book Okinawa Den Gojuryu Karate-Do, by Eiichi Miyazato (Jundōkan), which places the kakie in the chapter on supplementary exercises (hojo undō) and describes that “the purpose of the kakie is not simply a test of strength but rather an exercise in developing awareness and a sense of where your opponents hand is while you are pulling and pushing. (…) practitioners can both train overall muscular strength and at the same time develop dexterity.”[21] This differentiation is shared by researcher Naoki Motobu (Motobu-ryū): “I can say that Gōjū-ryū’s kakie is a ‘tempering method’ (tanren-hō) in which the arms are pushed and pulled with each other’s. The kakidī of Motobu-ryū, on the other hand, is a completely free kumite”.[22]

Also about Naha-te there is an important record preserved in the standard kumite form of the Tō’on-ryū, style of Jūhatsu Kyoda, who was the senpai of Chōjun Miyagi. The term kakedameshi is not used in this school (and it wouldn’t even make sense, given the challenge connotation of the term), but kake-kumite is. Kyoda preserved much of the Naha-te methods imparted by his master, Kanryō Higaonna, making few additions of kata and kihon exercises. Shigehide Ikeda, the current leader of Tō’on-ryū, states that “Kake-kumite is very important, it is to understand your opponent and how to treat him, his weak and powerful sides and also your own.”[23]

The more detailed technical descriptions of kake-kumite/kakedameshi dynamics are predominantly in line. Deepening the approach of Naha-te/Tō’on-ryū, an interview given by Shigekazu Kanzaki (Ikeda’s predecessor as head of the style) to researcher and translator Mario McKenna brings a precious record about it[24]:

Instead of prearranged sparring [yakusoku-kumite], Juko Sensei and I practiced free sparring [jiyū-kumite]. This method involved placing your right wrist on the right wrist of your partner’s while both would assume a right forward stance. The left fist was held at the waist. Kyoda Sensei would stand between us and hold both of our fists down and we waited for our chance. It is exactly like the start of Japanese Sumo. You looked for your chance and with a shout “HA,” the sparring would start. In other words, Tou’on-ryu is a style that favors close-in fighting and the use of techniques at an extremely close distances. Therefore, we do not do prearranged sparring where an attack comes and you block in a certain manner and attack a certain manner.

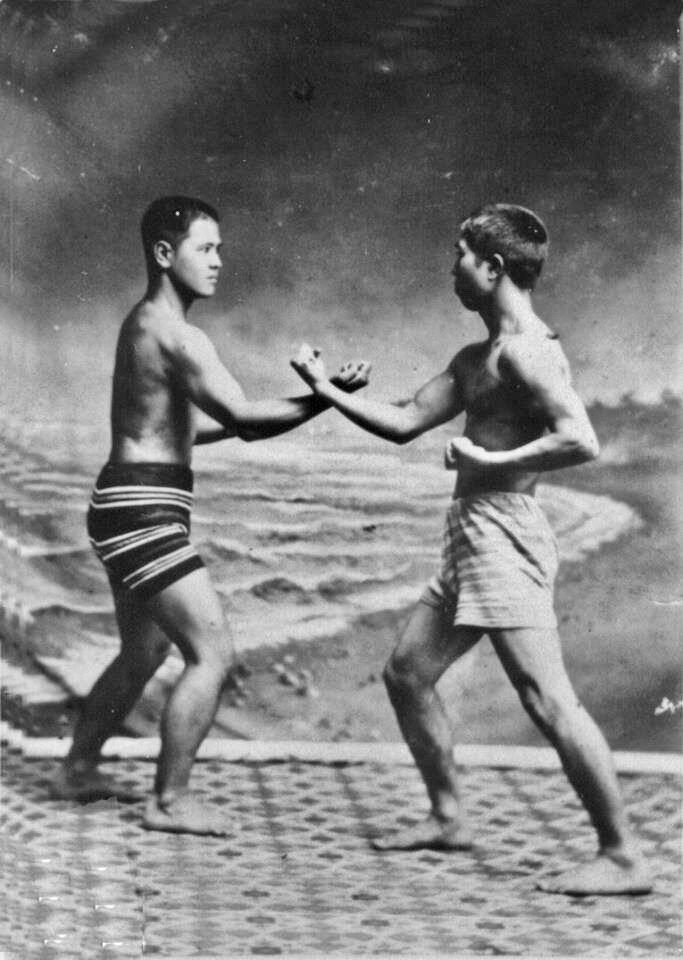

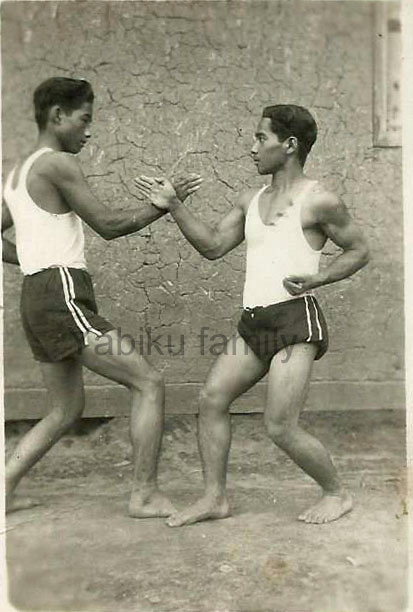

We can observe that the above description matches the one presented previously in Motobu-ryū with the definition of practice, both in the aspect of short distance and in the initial position with kakete. In fact, Kanzaki’s description fits perfectly with a very important historical photo, precisely showing young Chōjun Miyagi and Jūhatsu Kyoda[25]:

Referring to the photo of Miyagi and Kyoda, in another interview, Kanzaki also states that “from this stance all techniques of attacking and defending were practiced.”[26] Along the same lines, in the Motobu-ryū definition for kakidī/kake-kumite[27] mentioned above in this article, one of the photos used to portray the position of the practice is this one, as follows:

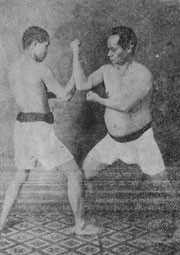

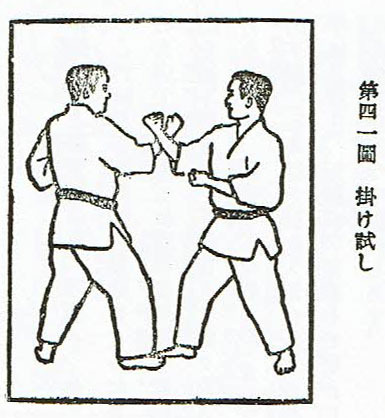

This is the classic position at the beginning of the beginning of kake-kumite/kakedameshi and also refers to the bridge example illustrated earlier by Russ Smith. Another reference that confirms this is from Genwa Nakasone and Kenwa Mabuni (founder of Shitō-ryū) who in their book Kōbō Kenpō Karate-Dō Nyūmon (Introduction to Karate-Dō: Offensive and Defensive Fist Method, 1938)[28], when defining kakedameshi, present the image below:

As we can see, the position is almost identical. In their description, Mabuni and Nakasone write that from this kakidī/kakete posture “you never know how the opponent will transition.” They also say that, “in Okinawa, they call it kake-dameshi, and they often try to ‘hook’ (hikkake) good techniques to each other”, so that both practitioners can understand their abilities.

An older reference to kakedameshi is related to Sokon Matsumura (Shuri-te), when he was 17 or 18 years old (circa 1827). In his book Empty Hand: The Essence of Budo Karate Kenei Mabuni (son of Kenwa Mabuni) tells a version of the story of how Matsumura would have confronted his future wife twice in kakedameshi,when she would have emerged victorious from the first confrontation and he won the rematch[29]. The report starts as follows:

At that time a rumor reached the ears of Matsumura from Shuri that the mayor of Yonabaru had a very beautiful 15 year old daughter called Ume. She was not only blessed with beauty and reason but also said to be quite good in fighting. Her father was reported to have offered her saying: “The man who can win a fight (kake dameshi) against her will be allowed to marry her.”

Another record has to do with Matsumura and his student Kentsū Yabu. Yabu emphasized the practice of kumite and said that “kata is born from kumite.” An account of this master, brought by Jisaburō Miki and Mizuho Takada in the book Kenpō Gaisetsu 拳法概説 (Introduction to Kenpō)[30], explains about the dynamics of training with Matsumura:

As a young man, he [Kentsū Yabu] often engaged in actual fights and sometimes went to other dojos to challenge them. Yabu Sensei’s practice method was to repeat a kata three or four times and then engage in a practice match – without any protective gear – against Matsumura Sensei, Yabu Sensei’s master.

A curious fact related to kake-kumite in the Matsumura/Yabu lineage is that there is a evidence of its practice in Brazil. This is the photo below, of students of Mōtoku Yabiku, disciple of Yabu. As I have mentioned in other texts, Yabiku immigrated to Brazil in 1917[31] and established himself as an important figure for the Uchinānchu (Okinawan) community in the country, but so far there are only records of him teaching Karate more than 30 years after his arrival.

As we can see, except for a minor variation (the open hands), the image is very similar to others already presented on kake-kumite/kakedameshi, including the photo of Chōjun Miyagi and Jūhatsu Kyoda. In Motobu-ryū, there is also variation in the kake-kumite position with open hand, which shows that the most important point of this dynamic is the establishment of the bridge (kakete)[32]:

Unfortunately, Mōtoku Yabiku passed away in 1951[33], shortly after starting to teach and promote Karate openly in Brazil. His students did not continue the school, which could have been a notable preservation of Karate from Kentsū Yabu. Anyway, the surviving records bring interesting clues about the history of Karate.

Kentsū Yabu and Chōki Motobu were friends, colleagues under Ankō Itosu’s guidance and shared a preference for kumite-oriented Karate. Some sources report that these two masters would have faced each other, with Yabu coming out the winner. According to Richard Kim, “the air cracked with the sound of loud kiai, feet shuffling, punches and kicks landing on human flesh, and the excited gasps of the few privileged viewers.”[34] Given the circumstances and context of the event, it is safe to say that this was a kakedameshi confrontation.

About the above account, evidence that reinforces the idea that it was kakedameshi is the presence of witnesses. In this sense, the description of the practice that is provided by Kenei Mabuni is important. In his book, he talks about the old way of fighting and about the involvement of his father, Kenwa Mabuni, with this type of confrontation[35]:

Young people who practiced karate made real-fight exercises called kake tameshi. Students who wanted to check themselves in such a test fight had to apply for and to ask witnesses to attend. One of the witnesses would act as referee. Then they would meet at an appropriate place in the streets, surrounded by their fellows. At that time there were no street-lights. So, when the sun had set, the opponents had to fight in the light of the lanterns held by the bystanders. The referee stopped the fight according to the situation and gave advices like: “You should practice this and that a little more…” Finally the technical abilities were discussed among the fellows.

My father, too, was often invited to such test fights and asked to serve as a referee for his friends. But the kake tameshi were not competitions like today. It was serious, real fight and “everything was allowed” but an opponent was never beaten up inexorably. Both opponents served each other to study their own weak and strong points. It was not “competing against each other” but “cooperating with each other”.

The issue of kakedameshi being a kind of free but controlled confrontation at a certain level is also reinforced by a speech by Chōfu Ōta at a meeting of masters in 1936. At one point Ōta recalls that in his youth he challenged Chōki Motobu to a “real fight”, but this one refused. Then Ōta comments that “in the olden days, martial artists would never fight unless they saw their opponent as a capable opponent. The actual fighting was done to test one’s own abilities, which is completely different from being violent.”[36]

The popularity of kakedameshi can also be attested by reports related to other masters such as Chōtoku Kyan. In his book Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters[37], Shōshin Nagamine wrote that Kyan “rarely, if ever, refused any challenge” of kakedameshi, “a popular practice among confident men of karate.” Nagamine himself claims to have had contact with this type of old practice:

Most, if not all, teachers of karate placed more emphasis on kakedameshi (fighting) than they ever did on the inward journey. In spite of disliking such practices, I first learned karate under these circumstances.

There are even indications that Gichin Funakoshi was involved in kake-kumite/kakedameshi. The main one is a Chōki Motobu’s account of a confrontation between the two: “I grabbed his hand, took up the position of kake-kumite and said “What will you do?” He was hesitant, and I thought to punch him would be too much, so I threw him with kote-gaeshi at which he fell to the ground with a thud.”[38]

It is also said that Yūchoku Higa (Shōrin-ryū Kyudōkan) “was the star of numerous Kakidamishi (combat challenges), increasing his physical, mental and spiritual attributes through intensive training sessions.”[39] Another report is related to master Tsuyoshi Chitose (founder of Chitō-ryū) and highlights not only the popularity, but the technical relevance of this type of practice[40]:

O Sensei loved to put his skills to the test in kakedameshi (field combat). He would often challenge other martial artists both unarmed and armed to fight. As a result he skills were not just theoretical, they really worked.

As we can see, the question of testing and polishing the skills and applications of Karate, whether in challenges or in practice in the dojo, combined with kata, are fundamental points of kake-kumite/kakedameshi. This seems something natural for an art that purports to be efficient for the real fight aimed for self-defense, evidencing a more pragmatic aspect of old Karate. In this sense, kake-kumite/kakedameshi is linked to the technical refinement of the art. Kanken Tōyama (Shūdōkan) states that “the experts and masters of Okinawa added the last finishing touches to karate by privately struggling through the hardships of ‘kaki dameshi’ かき試し {real bouts or matches 真剣試合}.”[41] According to historian Kōzō Kaku, “The tradition of kakedamashi (match fighting to test/improve skill) is a vital part of karate handed down in Okinawa and helps to improve their practical fighting skills.”[42]

It is worth mentioning that there are at least two reports involving the term kakedameshi that escape the prevailing descriptions. Both are by Gōjū-ryū masters, Morio Higaonna (IOGKF) and Seikichi Toguchi (Shorei-kan). In his book Okinawan Traditional Karatedo — Okinawa Goju Ryu Vol. 4, Morio Higaonna tells a story that would have happened in 1893, in which Kanryō Higaonna was suddenly attacked in Tsuji-machi by a troublemaker named Tokeshi Zencho[43]. Toguchi’s account in Okinawan Goju-Ryu II: Advanced Techniques of Shorei-Kan Karate also involves sudden attacks on renowned karateka by people seeking fame[44]:

Seyu (Kaka) Nakasone of tomari-te was a carpenter by trade. He was once attacked by a man while working. Nakasone instantly blocked the assailant’s attack and simultaneously struck the man on the head with a hammer he was holding. The man was knocked unconscious and hospitalized.

Seko Higa and Chosin Chibana of shorin-ryu were constant targets of kakidameshi. I was challenged quite often and therefore always walked close to the left side of the road so as to never leave my left side open. I became especially careful at corners, where attacks often occurred. (…) Nowadays these attacks seem unbelievable, but it was a true part of karate life in Okinawa back then. (…) Although I never looked for a fight, I was always forced into one.

The accounts of Higaonna and Toguchi seem to make an extensive but less precise use of the language, in which the word kakedameshi is used for any kind of test of strenght, without considering the semantics of “test by kake”, which is in turn incompatible with sudden and not consensual attacks. In any case, these forced and recurring fights were also a means of forging skills, because of an inherent need of it, as Toguchi says: “in the frequent engagement of kakidameshi, I gained great insight and experience that helped me in developing the shorei-kan system.”

3. Chinese analogues of kake-kumite/kakedameshi

As already mentioned when defining the term kakete, its dynamics and scope, this approach refers to Chinese martial arts styles, which in turn are a large direct influence for Karate. Forms of kumite from China have been present in Okinawa at least since the 18th century, as evidenced by the historical record of the term jiāoshǒu 交手 (“exchange of hands” or simply fighting) which, according to Andreas Quast, was “used in the 1719 report of the Sappōshi [Xu Baoguang] as well as in the 1867 program of the Kume School.”[45] There is also the 1762 Ōshima Hikki report, which describes a demonstration by a Chinese official identified as “Kūsankū” and his disciples.[46]

A form of fighting similar to kake-kumite can be found in styles such as Hung Gar[47] and Taiji (Taichi)[48], with the name of Sànshǒu 散手 (scattered/free hands). Performing this exercise has different levels of “practicality” depending on the school, but the characteristic dynamic involves close range and contact, even starting with the practitioners’ arms crossed in a similar fashion to the old Okinawan combat. I note that Sànshǒu is also another name for Sǎndǎ 散打, a form of full contact Chinese boxing (in this case, a modern sport).

Hung Gar Sànshǒu

Chinese arts with a closer connection to Karate, originating from the Fujian region, also take an approach similar to kake-kumite. More specifically the variations of the Bái Hè Quán 白鶴拳 (White Crane Fist), style represented in one of the most important historical documents of Karate, the Bubishi. An example of this dynamic is present in the sparring (duì dǎ 对打/對打) of the Míng Hè Quán 鳴鶴拳/鸣鹤拳 (Whooping Crane Fist).[49] [50] This style is the same one that, according to researcher Patrick McCarthy[51], was founded by Ryū Ryū Ko (nickname of Xie Zhongxiang), who in turn would have been one of the teachers of Kanryō Higaonna, exponent of Naha-te and master Chōjun Miyagi, Jūhatsu Kyoda and Kenwa Mabuni.

Míng Hè Quán

Kake-kumite can also be related to Wing Chun exercises like Chi Sau 黐手 (sticking hands)[52] and Lap Sau 擸手 (grabbing hands), among others, mainly due to the close range dynamics, connection between techniques and constant contact between practitioners. According to Yip Chun, after learning the forms, the practitioner “can apply these techniques in free fighting. This is the ‘bridging’ function of Chi Sau. Once you have learned the techniques through Chi Sau, you can deal with any fighting situation.”[53] It is relevant to note that similar concepts, due to the dynamics of applications from connections such as kakete, are also present in Southeast Asian arts, like Kali and Silat.

4. Summary of the technical scope of kake-kumite/kakedameshi

Based on historical accounts and how the practice survived in some styles, as presented throughout this article, it is possible to define the basic methods of kake-kumite and its objectives:

1. It’s a form of free sparring. The general idea of kake-kumite involves free testing of karate combat techniques, as pointed out in accounts such as Motobu-ryū, Tō’on-ryū and Kenei Mabuni.

2. Emphasis on close range from kakete. This type of combat, being based on kakete, by itself already shows a dynamic that favors contact and the establishment of bridges. This is fully in line with using historical Karate concepts such as muchimi 餅身[54], which are based on close range grip, opponent control and tactile sensitivity.

3. Includes strikes and grappling. The scope of free combat at close range shows that in addition to elbow strikes, punches and kicks joint lock techniques, twists and throws are included, taking advantage of all the technical potential of Karate. As already mentioned, there is a story in which Chōki Motobu would have applied kote-gaeshi to Gichin Funakoshi. Old accounts that compare Karate to a “mixture of boxing and jujutsu”[55] are also relevant, such as the performance of Kentsū Yabu in Hawaii in 1927, making clear the versatility of the techniques developed.

4. Despite the free format, the techniques are applied with control. Reports such as of Kenei Mabuni and Chōfu Ōta make it clear that, even in the kakedameshi challenge practice, kake-kumite was developed in such a way that the techniques could prove successful, but without the purpose of knocking out or physically destroying the opponent. This can also be seen in the analogs existing in Chinese practices, where the use of sundome 寸止め (stop the strike at a minimum distance is evident — in this case, different from the form of sundome applied in modernly in jiyū/shiai-kumite, where the strikes they are often fully extended, but due to the greater distance they do not reach the opponent, or touch without deepening the blow into the opponent’s body).

5. It can be used to measure strength and skill with another practitioner. Historical accounts make it clear that kakedameshi was a consensual confrontation, and that a person could refuse a challenge if he did not consider the adversary to be a “capable opponent”. It is logical to think that, in a skill test to improve one’s technique, a person would look for opponents who could provide this feedback and, at the same time, determine who is at a higher level.

6. The purpose of the confrontation is not mere competition, but collaboration. As described in the reports about kakedameshi, the confrontation was made with witnesses, a kind of judge and at the end of the fight, not only a winner was determined, but was also pointed out where the practitioners could improve. This indicates that kakedameshi served not only as a means to settle “rivalries”, but also as a form of technical exchange.

7. It is a type of kumite that is directly related to the kata. Masters involved in the practice of kake-kumite/kakedameshi, such as Kentsū Yabu, pointed out that the relationship between kata and kumite was inseparable. As already mentioned, in training with Kōsaku Matsumora, Yabu would practice kata a few times and then practice kumite. Eiichi Miyazato says in his book that “In days past, kata and kumite were said to be like wheels on a car.”[56] This statement by Miyazato agrees with one by Funakoshi: “Needless to say that kumite should not be independent and separate from kata, since every kata is applied in kumite. Therefore, sacrificing kata for the sake of kumite should never be allowed to happen.”[57]

8. It is a method of pressure testing techniques practiced in solo training. It is evident from the records and references on kake-kumite/kakedameshi that in addition to being a way of measuring and developing skills, dynamics is also a method for testing Karate applications. Based on the assumption that a complete karateka seeks a certain level of pragmatism for what is developed in Karate training, it is necessary to train the skills and hypotheses of application with opponents who offer some level of active resistance, to understand what works and under what conditions. This is particularly important when studying the applications of kata (bunkai 分解) in a serious and realistic way.

It is important to emphasize that, in addition to all the above descriptions about kake-kumite, a ninth item can be added: the practice is also aligned with the original purpose of Karate, which was civil self-defense. As Chōjun Miyagi wrote: “according to oral history, in the old days, the teaching policy of karate put emphasis on self-defence techniques.”[58] This is manifested in kake-kumite through the close range approach and opponent control, tactical principles of self-defense. As Rory Miller points out[59]:

One of the most common and artificial aspects of modern martial arts training is that self-defense drills are practiced at an optimum distance where the attacker must take at least a half step to contact. Real criminals rarely give this luxury of time. They strike when they are sure of hitting, positive that their victim is well within range before initiating the attack.

(…)

The attacker always chooses the time and place for the attack, and he chooses a range at which he can surely hit hard and his victim will have the least possible time to react. This means he will be close.

Self-defense here is defined as a non-consensual physical confrontation, in which an aggressor wants to hurt you and you need to defend yourself. Of course, as part of Karate’s defensive purpose, close range dynamics is not a modern tactical concept. As Samir Berardo points out, “if you are really in a self-defense situation (and not in a street brawl or sports situation), you will almost always simply be forced to fight at close range. (…) In reality, it is often much easier to defend against an attacker at close range.”[60] This principle is confirmed by Shigekazu Kanzaki when describing the main lesson he learned from his master Jūhatsu Kyoda: “in the case of combative engagement distance being further away then it is best to avoid confrontation. Karate technique is a defensive skill used in close quarters and not meant to be used otherwise.”[61]

5. Modern kake-kumite/kakedameshi practice

As previously pointed out, the practice of kake-kumite is not very common in modern Karate and has persisted in few traditional schools. In an article from August 2020, researcher Naoki Motobu ponders that until that moment, he was only aware of this practice in his school Motobu-ryū, where this type of kumite is called Kakidī.[62] In the same article, he states:

Since kakidī makes free use of attack and defense, one can instantly react to an attack by the opponent and defend, or one can instantly attack without missing an opening provided by the opponent. This is because kakidī cultivates this kind of reflexes or quick reactions. These abilities are difficult to obtain by striking the makiwara by oneself or by practicing yakusoku kumite, which only performs predetermined actions.

It is notorious that the descriptions of Motobu-ryū fit with those provided by Shigekazu Kanzaki and Shigehide Ikeda of Tō’on-ryū already presented in this article. In the Tō’on-ryū references, it is also pointed out that the kake-kumite of this school involves ideas of instantaneous reaction to the opponent, close range and the development of skills not obtained with exercises such as yakusoku-kumite.

In addition to kake-kumite having withstood time and having been preserved in the aforementioned schools, known for its historical and technical relevance to Karate, modern organizations have made efforts to revive and popularize the practice. This movement is linked to a growing interest in a practical and functional approach to Karate[63] that has gained traction over the past two decades, for a number of factors. As already mentioned, kake-kumite is linked to principles related to self-defense, so it is reasonable that the search for a functional karate, in various parts of the world, provides rescue (consciously or not) of these methods, in a kind of zeitgeist.

In Brazil, there is the research society Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai, founded by Samir Berardo. Based on historical and technical investigation, this group has reconstructed the practice of kake-kumite and maintains it as a form of regular training among its members.[64] The practice in this organization, like what was listed in the previous section of this article, is used not only to measure forces, but as a tool for technical development and testing under pressure of the applications of the kata practiced and analyzed within this research society, serving also as part of a study method.

Kake-kumite at Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai

An example of a path similar to Muidokan can be found at Noah Legel’s Arizona Practical Karate school, located in the United States.[65] In this dojo the term kakedameshi is used. Texts and videos addressing the topic are frequently published by Legel. Also in the United States, Daniel Marino’s AmKor Karate Institutes Paoli dojo is another school where kakedameshi is practiced.[66]

Other schools of modern Karate, even not using the terms kake-kumite or kakedameshi, when looking for ways to train Karate in a practical way, end up developing kumite methods with similar proposals and objectives, even though technically there are differences. One example is the school of Iain Abernethy (UK), perhaps the best known name today for practical Karate, where there is a type of fighting called kata based sparring.[67]

A further important point to note is that even though most schools do not formally practice kake-kumite/kakedameshi, related principles of close range confrontation, connection, and control of the opponent are applied by highly regarded masters. One of them is Morinobu Maeshiro (Shidōkan), who informally applies a similar dynamic in his dojo in Okinawa.[68] Even the way kakie is conducted in some schools, as a more contained form of sparring, incorporates kake-kumite principles and is a vestige of the transmission of its concepts.

Another relevant observation is that the terms kake-kumite and kakedameshi are also used in Japan by some modern organizations, but in a limited way compared to the original purpose or in a modern full contact format. Examples of these groups are the Takaku Dojo (高久道場)[69], the Saitama Kakedameshi Keikokai (埼玉掛け試し稽古会)[70] and the Fukushima branch of the Shinkyokushinkai (新極真会 福島支部).[71]

As pointed out earlier in this article, the term irikumi also has a semantic and historical relationship with kake-kumite, although it is modernly interpreted in different ways depending on the school. As a form of combat, irikumi currently develops as a modern jiyū-kumite format in the organizations Jundōkan and IOGKF[72], where it is also applied competitively. At Shoreikan school, irikumi[73] is a “real combat practice, but was set up in such a way so students were not injured.”[74] It is also worth mentioning that at Meibukan school[75] there is a form of free kumite, applied in full contact.

6. Conclusion

Throughout this article I discussed historical and technical aspects of kake-kumite, kakedameshi and kakete/kakidī, drawing a definition for each of these concepts, the general scope and even how some vestiges of these practices are present in Okinawan Karate. I also discussed how these concepts are related to Chinese martial arts, especially Fujian styles. For this purpose, the resources were video records, interviews, articles and also books by renowned authors such as Patrick McCarthy, Shōshin Nagamine, Andreas Quast, Naoki Motobu, Kenei and Kenwa Mabuni, among others. Finally, I also discussed modern initiatives for the reconstruction and revival of the practice of kake-kumite/kakedameshi.

My goal with all this was to bring a presentation of what kakete, kake-kumite and kakedameshi are to a wider audience, what are its characteristics and possible benefits. Personally, having had direct contact with kake-kumite in one of the organizations mentioned in this article (Muidokan), I believe that understanding and developing exercises of this type is essential for karateka who seek to explore Karate in a functional way. From this experience, I observe that through kake-kumite it is possible to understand the concepts conveyed in the kata and to test application hypotheses. This aligns perfectly with historical aspects because, quoting once again Shigekazu Kanzaki’s speech, Karate (as recorded in the kata) is an art meant to be used “in close quarters and not meant to be used otherwise”. Over the years and the popularization of Karate, other approaches and uses emerged, being suitable for other contexts, but the historical foundations should not be ignored or erased.

Ways of putting to the test applications of what is intended to be called “bunkai” are essential, as applying a technique with an opponent who does not react, in an unrealistic scenario, in no way validates any theory. According to Eiichi Miyazato, “students must dissect the kata and research and practice the individual techniques using them in kumite.”[76] Pressure testing and validation is even more important when applications are labeled as self-defense, as those involve risk to the physical integrity of practitioners when are needed in a real situation. Evidently, kake-kumite alone does not cover all needs of preparation and testing, but it is a very useful historical tool for this purpose.

I note that, when approaching kake-kumite and its context, I do not do so in demerit of modern kumite forms, competitive formats or modern methods of Karate as a whole. Karate is a plural art, with several approaches and possibilities. To be able to differentiate them and know exactly what is being trained and why, historical context and technical repertoire are necessary. Naturally, even schools considered more traditional combine old methods with more modern forms, according to their purposes, whether in supplementary exercises (hojo undō), in the performance of kata and also in kumite.

Ironically, I notice that some people with high belt ranks here in Brazil insist that there is no free kumite in Okinawan Karate, only yakusoku-kumite. As demonstrated, it is clearly an absurd (and somewhat embarrassing) statement that does not stand up to any minimal research, common sense or knowledge of Karate. Even though kakedameshi/kake-kumite/kakidī are not very common, they are linked to the roots of karate and demonstrate the intrinsic relationship of kata and application. There are historical records, as shown, of both challenge situations and kake-kumite training in Okinawan schools. Also as we have seen, even where the old-style approach has not been fully preserved, well-known Okinawan schools maintain elements of the old fighting approach in their exercises, in addition to practicing forms of jiyū-kumite and shiai-kumite with modern and very popular setups. In short, free kumite existed since the origins of Okinawan Karate.

Another curious fact is that, from the moment that the terms kake-kumite and kakedameshi gained a certain visibility in recent years, due to the work of researchers and people interested in practical/historical karate, people emerged stating that this is nothing new and that they have been practicing kakedameshi for 20 or 30 years. This kind of statement is doubtful to say the least since, as pointed out, kake-kumite and kakedameshi are something little known even in traditional schools or only survived in the form of stories. It is common, when certain issues are raised in the Karate community and when research is publicized, that these “missing links” suddenly appear, always knowing everything, acting as if everything is common knowledge, but have never demonstrated or mentioned anything before. Sometimes these statements provide evidence of little or no understanding of the subject. We increasingly need people who explore Karate sincerely and honestly, willing to learn, share, debate, complement and review their own perceptions about this art.

I note that, as much as this article brings enough descriptions and historical references of kake-kumite/kakedameshi to define well the concept and proposal of this practice, the theme is evidently not exhausted, both in technical details and in records. As other information proves pertinent to the general definition, as well as possible corrections, this article may undergo updates and revisions. The idea is that this article will also be the starting point for further publication of materials that complement or address specific points related to kake-kumite, kakedameshi and kakete, as well as related elements, so that these concepts finally have the proper attention and understanding by the Karate community in a broad way.

It is important to mention that this article was made possible by an earlier initiative to study the functionality of Karate conducted by Samir Berardo and the group he founded, Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai. It was through contact with this work that I learned for the first time about the dynamics of kake-kumite/kakedameshi and related concepts, thus being able to explore the practice and, from that, develop my own studies. Otherwise, without support or contact with previous studies, it would certainly take me many more years to reach the same understanding and conclusions. In this sense, I would like to thank the group. I hope that all the collaborative work carried out by them will serve as an inspiration and bear many other fruits.

Finally, my hope is that this article will contribute to stimulate interest of other Karate practitioners on the subject, that they conduct their own research, submit the methods to testing or even look for organizations that already develop Karate study and practice with functional and historical foundations. In my view, this whole movement only has to elevate Karate, preserve its identity, its legacy and provide that the full potential of this art can be enjoyed by us and by the next generations.

[1] For this article, the system used for the romanization of Japanese/uchināguchi words is the revised Hepburn, with macron for indication of long vowels and apostrophe for separation of phonemes. In the case of direct quotes and reference notes, to keep the text faithful to the original, it was decided to follow the spelling used in the source.

[2] [Kakede] 掛け手. Motobu-ryu, 2007. Retrieved from: <https://www.motobu-ryu.org/本部拳法/本部拳法の技術体系/掛け手/>. Last accessed: March 31 of 2021.

[3] SMITH, Russ. Principle-Driven Skill Development: In Traditional Martial Arts. Spring House: Tambuli Media, 2018. E-book Kindle. p. 143.

[4] FUNAKOSHI, Gichin. Karate Do Kyohan: Master Text for the Way of the Empty-Hand. Neptune Publications, 2005. p. 146.

[5] MCCARTHY, Patrick. Kanzaki Interview. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society, 2001.

[6] Burinkan Martial Arts, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://www.facebook.com/BurinkanDojo/photos/a.1075490102837482/1075490186170807>. Last accessed: May 10th of 2021.

[7] DENWOOD, Chris. Kakiya – The Okinawan Wooden Man. Chris Denwood Living Karate, 2014. Retrieved from: <https://www.chrisdenwood.com/blog/kakiya-the-okinawan-wooden-man>. Last accessed: May 19th of 2021.

[8] hand. jisho. Retrieved from: <https://jisho.org/search/%E6%89%8B%20%23kanji>. Last accessed: July 30th of 2021.

[9] MOTOBU, Naoki. Kin Ryōjin and Motobu Chōki. 本部流のブログ, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12673327802.html>. Last accessed: May 8th 2021.

[10] HIGAONNA, Morio. Okinawan Traditional Karatedo — Okinawa Goju Ryu Vol. 4: Applications of the Kata Part 2. Minato Research/Japan Publications, 1991. p. 135.

[11] MCCARTHY, Patrick. Motobu Choki’s “My Art of Karate”. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society: 2019. p. 144.

[12] MOTOBU, Naoki. Kumite of the University of Tokyo. 本部流のブログ, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12665059384.html>. Last accessed: May 2nd of 2021.

[13] NAKAYAMA, Masatoshi. Best Karate 1: Comprehensive. New York: Kodansha International, 1977. p. 112.

[14] FUNAKOSHI, Gichin. To-te Jitsu. Hamilton: Masters Publication, 1997.p. 55.

[15] FUNAKOSHI, Gichin. Karate Do Kyohan: Master Text for the Way of the Empty-Hand. Neptune Publications, 2005. p. 146.

[16] NAGAMINE, Shōshin. Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 2000. E-book Kindle.

[17] QUAST, Andreas. On Kakidī. Ryukyu Bugei 琉球武芸, 2015. Retrieved from: <https://ryukyu-bugei.com/?p=3794>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[18] OSHIRO, Toshihiro. Interview: Shuichi Aragaki. Dragon Times. Retrieved from: <https://www.dragon-tsunami.org/Dtimes/Pages/article41.htm>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[19] Kyudokan 1968 Yuchoku Higa: Kakie. 2016. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8d2BYO_QaCQ>. Last accessed: April 5th of 2021.

[20] BERARDO, Samir. What is kakie? How does it work?. Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://muidokan.com/what-is-kakie-how-does-it-work/>. Last accessed: April 5th of 2021.

[21] MIYAZATO, Eiichi. Okinawa Den Goju Ryu Karate-Do. Naha: Okinawa Goju Ryu Karate-do So Honbu Jundokan, 2005. p. 44.

[22] MOTOBU, Naoki. Records about Kakidī before WWII. 本部流のブログ, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12616358770.html>. Last accessed: April 1st of 2021.

[23] DEMYANOV, Pavel. Тоон-Рю Интервью / Touonryu Interview / 2019 (Bilingual). Рюсёкай Годзю-Рю Каратэ-До, 2019. Retrieved from: <http://ryusyokai.ru/blog/touonryu-interview-2019/>. Last accessed: April 12th of 2021.

[24] MCKENNA, Mario. Tou’on Ryu: The Karate of Juhatsu Kyoda Part 2. Classical Fighting Arts Magazine – Vol 2 No 21 Issue 44, 2011.

[25] [Gōjū-ryū Shi] 剛柔流史. 沖縄剛柔流空手古武道拳志會山口県支部, 2019. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/ryukyukobujutsu/entry-12490746561.html>. Last accessed: April 29th of 2021.

[26] MCKENNA, Mario. Kanzaki Shigekazu: An Interview with To-on-ryu’s Leading Representative. Journal of Asian Martial Arts – Vol 9 No 3, 2000. pp. 32-43.

[27] [Kakede] 掛け手. Motobu-ryu, 2007. Retrieved from: <https://www.motobu-ryu.org/本部拳法/本部拳法の技術体系/掛け手/>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[28] MOTOBU, Naoki. Records about Kakidī before WWII. 本部流のブログ, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12616358770.html>. Last accessed: April 1st of 2021.

[29] MABUNI, Kenei. Empty Hand: The Essence of Budo Karate. Chemnitz: Palisander Verlag, 2009. E-book Kindle. pp. 156-157.

[30] MOTOBU, Naoki. Yabu Kentsū’s View of Kumite. 本部流のブログ, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12662155548.html>. Last accessed: May 2nd of 2021.

[31] About the arrival of Karate in Brazil. Puro Karate, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://purokarate.com.br/en/2020/05/15/about-the-arrival-of-karate-in-brazil/>. Last accessed: May 17th of 2021.

[32] [Kakede] 掛け手. Motobu-ryu, 2007. Retrieved from: <https://www.motobu-ryu.org/本部拳法/本部拳法の技術体系/掛け手/>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[33] About the arrival of Karate in Brazil. Puro Karate, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://purokarate.com.br/en/2020/05/15/about-the-arrival-of-karate-in-brazil/>. Last accessed: May 17th of 2021.

[34] SVINTH, Joseph R. Karate Pioneer Kentsu Yabu, 1866-1937. EJMAS, 2003. Retrieved from: <https://ejmas.com/jcs/jcsart_svinth_0603.htm>. Last accessed: May 30th of 2021.

[35] MABUNI, Kenei. Empty Hand:The Essence of Budo Karate. Chemnitz: Palisander Verlag, 2009. E-book Kindle. p. 120.

[36] MOTOBU, Naoki. Kakedameshi. 本部流のブログ, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12589792105.html>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[37] NAGAMINE, Shōshin. Tales of Okinawa’s Great Masters. Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing, 2000. E-book Kindle.

[38] MCCARTHY, Patrick. Motobu Choki’s “My Art of Karate”. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society: 2019. p. 52.

[39] Yuchoku Higa – Shorin-Ryu. Shuriway Karate & Kobudo Website. Retrieved from: <https://www.shuriway.co.uk/higa.html>. Last accessed: May 3rd of 2021.

[40] Chito-Ryu Karate-Do. Karate 4 Life. Retrieved from: <https://karate4life.com.au/chito-ryu-karate-do/>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[41] TOYAMA, Kanken. Introduction to Karate-Do: It’s Inner Techniques and Secret Arts. Seattle: Tobey Stansbury, 2019. p. 8.

[42] MCCARTHY, Patrick. On Choki Motobu – Part 2. FightingArts.com. Retrieved from: <http://www.fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=400>. Last accessed: March 31st of 2021.

[43] HIGAONNA, Morio. Okinawan Traditional Karatedo — Okinawa Goju Ryu Vol. 4: Applications of the Kata Part 2. Minato Research/Japan Publications, 1991. p. 168.

[44] TOGUCHI, Seikichi. Okinawan Goju-Ryu II: Advanced Techniques of Shorei-Kan Karate. Midwest City: Black Belt Publishing, 2018. p. 35, 36.

[45] QUAST, Andreas. A Stroll Along Ryukyu Martial Arts History. Düsseldorf: 2015. E-book Kindle. p. 208.

[46] QUAST, Andreas. Nakahara Zenshu: Character and Weapons of the Ryukyu Kingdom (5). Ryukyu Bugei 琉球武芸, 2015. Retrieved from: <https://ryukyu-bugei.com/?p=3930>. Last accessed: May 17th of 2021.

[47] Hung Gar San Shou (洪家拳种-散手对練). 2011. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wiXMGFicwo0>. Last accessed: May 13th of 2021.

[48] Taiji Fighting Set (Taiji San Shou Dui Lian, 太極散手對練). 2019. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UD1hRxA5b4M>. Last accessed: May 13th of 2021.

[49] Whooping Crane Master Yu Dan Qiu – Masters of Fujian ep8. 2020. Retrieved from: <https://youtu.be/dEKv04UZ6cc?t=935>. Last accessed: May 17th of 2021.

[50] [Míng hè quán duìdǎ] 鸣鹤拳对打. 2015. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Me28qOk-2G0>. Last accessed: May 17th of 2021.

[51] MCCARTHY, Patrick. Bubishi: Classic Manual of Combat. Rutland: Tuttle Publishing, 2016. p. 131.

[52] [Hong Kong Wing Chun Chi Sao Bǐsài (yī)] 香港第一屆詠春拳黐手比賽 (一).2017. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nQN9BKyfPIw>. Last accessed: May 13th of 2021.

[53] CHUN, Yip. Wing Chun Martial Arts Principles & Techniques. Weiser Books, 1993. E-book Kindle. p. 42.

[54] QUAST, Andreas. Muchimi. Ryukyu Bugei 琉球武芸, 2015. Retrieved from: <https://ryukyu-bugei.com/?p=4809>. Last accessed: May 19th of 2021.

[55] Account about Kentsu Yabu in Hawaii, in 1927, describes Karate as a ‘mixture of boxing and wrestling’. Puro Karate, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://purokarate.com.br/en/2021/03/17/account-about-kentsu-yabu-in-hawaii-in-1927-describes-karate-as-a-mixture-of-boxing-and-wrestling/>. Last accessed: March 17th of 2021.

[56] MIYAZATO, Eiichi. Okinawa Den Goju Ryu Karate-Do. Naha: Okinawa Goju Ryu Karate-do So Honbu Jundokan, 2005. p. 147.

[57] FUNAKOSHI, Gichin. Karate Do Kyohan: Master Text for the Way of the Empty-Hand. Neptune Publications, 2005. p. 146.

[58] MIYAGI, Chōjun. Historical Outline of Karate-Do, Martial Arts of Ryukyu. Sanzinsoo Okinawa Goju-Ryu Karate-Do, 2007. Retrieved from: <http://yamada-san.blogspot.com/2007/12/under-construction.html>. Last accessed: March 15th of 2021.

[59] MILLER, Rory. Meditations on Violence: A Comparison of Martial Arts Training and Real World Violence. Wolfeboro: YMAA Publication Center, 2014. E-book Kindle.

[60] BERARDO, Samir. Defensive power of historical karate techniques in close range fighting. Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://muidokan.com/defensive-power-of-historical-karate-techniques-in-close-range-fighting/>. Last accessed: May 8th 2021.

[61] MCCARTHY, Patrick. Kanzaki Interview. International Ryukyu Karate Research Society, 2001.

[62] MOTOBU, Naoki. Records about Kakidī before WWII. 本部流のブログ, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://ameblo.jp/motoburyu/entry-12616358770.html>. Last accessed: April 1st of 2021.

[63] The Functional Karate Revolution, 2020. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvqYqOpjlIg>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[64] BERARDO, Samir. Video: kakedameshi, historical teachings of karate and hontou bunkai. Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://muidokan.com/kakedameshi-historical-teachings-of-karate-and-hontou-bunkai/>. Last accessed: May 1st of 2021.

[65] Arizona Practical Karate. Karate Obsession, 2019. Retrieved from: <https://www.karateobsession.com/az-practical-karate>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[66] The Naihanchi Project, 2021. Retrieved from: <https://www.facebook.com/naihanchiproject/posts/164821168977167>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[67] Practical Kata Bunkai: Kata Based Sparring. 2018. Disponível em: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wA3ZLONLq50>. Last accessed: May 22nd of 2021.

[68] Fist of Shuri, 2019. Retrieved from: <https://www.facebook.com/369876493765738/videos/292359364792411>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[69] [2019 09 14 Toyama Kakedameshi Keikokai Technical Hand ganmen ari 1] 2019 09 14 富山掛け試し稽古会 テクニカルハンド顔面有り1. 2019. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bZCNKk63BNc>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[70] [Saitama Kakedameshi Keikokai] 埼玉掛け試し稽古会. 2020. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x-LQ9oJ8Qz4>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[71] [【Shinkyokushinkai】 Fukushima Shibu Takahashi Yutaka Kake-kumite1]【新極真会】 福島支部 高橋豊 掛け組手1. 2016. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oEj4lrWJ7lQ>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[72] IOGKF Shurenkai Tokyo / 1st-2nd Dan Irikumi. 2008. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wIZ0_RWCiXs>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[73] [Okinawa Gōjū-Ryū Karate-Dō Shoreikan Hirakawa Dōjō] 沖縄剛柔流空手道 尚禮館 平川道場 Gojuryu Shoreikan Hirakawa Dojo. 2018. Retrieved from: <https://www.facebook.com/gojuryushoreikan/posts/496276430882471>. Last accessed: May 26th of 2021.

[74] NAITO, Ichiro; LENZI, Scott. The History and Evolution of Shorei-Kan Goju-Ryu Karate. Black Belt Vol 22 Nº 4, 1984.

[75] Goju-ryu Karate Sparring | Sport Kumite & Full contact | スポーツ組手&フルコンタクト空手 | 沖縄伝統空手. 2019. Retrieved from: <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=63c3KwGQT4I>. Last accessed: May 20th of 2021.

[76] MIYAZATO, Eiichi. Okinawa Den Goju Ryu Karate-Do. Naha: Okinawa Goju Ryu Karate-do So Honbu Jundokan, 2005.p. 67.

Pingback: Kake-Kumite/Kakedameshi: A forma original de confronto livre do Karate

Pingback: Fundamental technical concepts of old style karate – Muidokan Karate Kenkyukai

Me encantó esta publicación ya que muchos maestros y practicantes de Karate no conocen las verdaderas técnicas de este maravilloso arte y solamente conocen la parte deportiva.

Tantos elementos ocultos guardan sus técnicas.

Querido Zacha:

Me alegra que hayas disfrutado del artículo.

No olvides echar un vistazo a otras publicaciones en nuestra página web y no dudes en preguntar sobre los temas que tratamos.

Por cierto, ¿has podido seguirnos en nuestras redes sociales? Estamos en Facebook, Instagram y X. Puedes encontrar los enlaces en los botones de la esquina superior derecha de esta página web, justo encima del botón “Subscribe”.

Saludos,

Samir